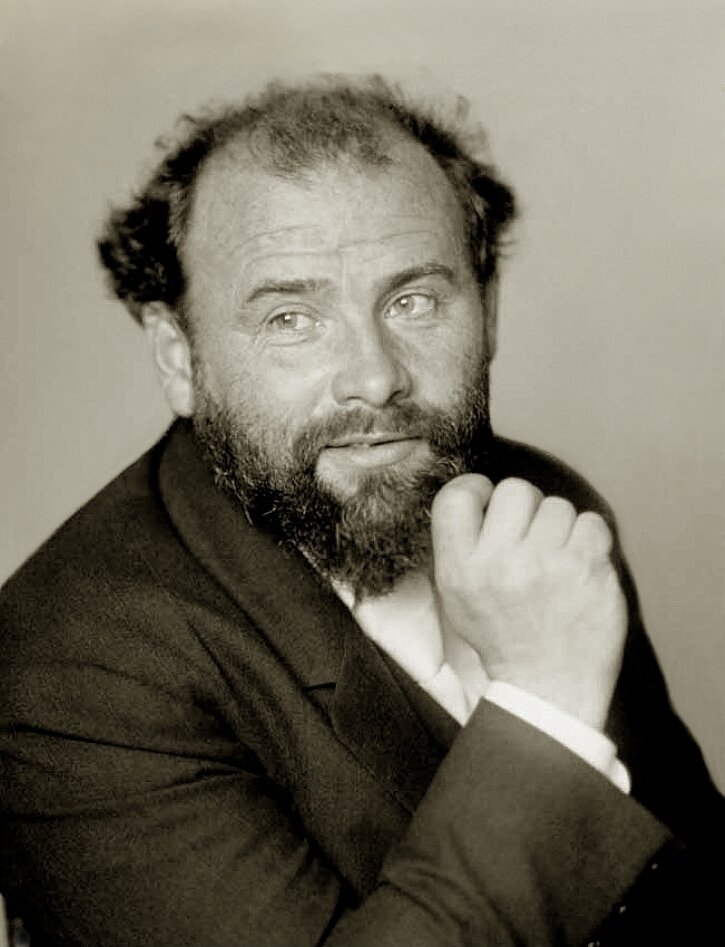

Nurturing The Natural Talent Of Gustav Klimt

The case of Gustav Klimt is one that epitomises the complexity of the Nature vs Nurture debate in creative talent.

Nature vs Nurture is the argument on whether a person was genetically predisposed to acquiring a specific characteristic or whether it was a product of their environment.

However, sometimes the origins of these characteristics may be hard to define as the line between nature and nurture becomes blurred.

The origins of artistic talent can be particularly challenging to discern.

Gustav Klimt was a renowned Austrian painter most well known for his painting ‘The Kiss’ (1907–1908), greatly influencing Vienna’s art history and the architecture of the city itself.

He was born into a poor family and was the second child of seven siblings. At an impressively early age, Gustav and his brother Ernest displayed incredible artistic gifts.

However, only Gustav proceeded to enhance and establish his talent.

Born to a failed-musical-performer mother and a gold engraving father, artisanal traits ran through the family.

Does this mean he was naturally gifted?

Although it is impossible to prove for his specific case, we can hypothesise from the several research findings that have supported the notion that artistic talent is tied to biology.

One study was done to compare the brain structure between 21 artists and 23 non-artists. It found that artists had more neural matter located in the areas of the brain linked to fine motor skills and visual imagery, implying that artistic talent is hereditary.

That’s not to say that practice doesn’t make perfect.

As a child, he was encouraged by a relative to pursue his gift. At the young age of only 14, he was enrolled at the prestigious University of Arts Vienna where he underwent intensive training in painting and drawing.

This placed him in an environment that groomed his artistic potential, further nurturing his innate talent.

In 1892 both his brother and father passed away, leaving him financially responsible to support his family.

Klimt began working tirelessly on public commissions, painting like his and his family’s life depended on it. Even in art as in nature, pressure creates diamonds.

He was offered a job to paint a mural within the University Of Vienna’s great hall, with the theme of ‘Medicine’.

The purpose of the mural was meant to celebrate medicinal achievement.

Instead, Klimt produced a heavily symbolic painting about the enigmatic unity between life and death, puzzling and angering the commissioners.

It was deemed too provocative and extremely controversial as it displayed highly sexualized nudity: Viennese society’s greatest taboo.

He was severely criticized for his work - attacked as ‘pornography’ - and caused the public to develop an extremely deprecatory view towards his art.

Due to this, the painting was never displayed, and he swore to never accept another public commission again.

Klimt then became conscious of the importance of nurturing his talent beyond the limitation of art experienced through the public domain.

At this point, it seems that natural talent had exceeded beyond what could be outwardly nurtured.

‘Polite society’ wasn’t able to keep up with his groundbreaking artistic expression.

The exploration of his talent had surpassed the tastes, limits and even the understanding of his end-of-century-culture.

Klimt was no longer a product of his environment. It was time for Vienna to be a product of him.

This revelation inspired him and his contemporaries to create the Vienna Secession, an art movement started in 1897 by the ‘Association of Austrian Artists’.

The goal was to develop a new leading association for young conventional artists.

Klimt understood the significance of the recognition and nurturing of talent.

He wanted to bestow these artists with the encouragement and freedom which the public could not provide, creating a safe space for them to explore and showcase their work.

This allowed them to operate at a level beyond what the environment could contend with, resulting in personal breakthroughs and permanently embalming them into Vienna’s cultural Zeitgeist.

Artistic talent may be difficult to develop without the basic genetic foundation.

However, any talent that is left un-nurtured may never reveal itself, further highlighting the complexity of the nature vs nurture debate.

Perhaps the two factors could not be seen as two opposing ends of a spectrum - but instead, a complimentary double helix.

An artistic talent’s realised potential requires a symbiotic balance of both nature and nurture.

Indeed, Klimt was the guardian who had the courage to build a haven that nurtured the natural talent of the city’s young artists.

This revolution played a significant role in sculpting Viennas art culture, infusing Klimt’s name, work and style into the city’s DNA.